The above collection (originally titled Old Houses) was part of a group exhibition in 2006 at the Portuguese Consulate in Goa. The “Goa Photogs,” a group I co-founded in 2004 along with a few photo enthusiast friends, was invited by the then Consul General to exhibit at the Consulate in Goa. The exhibition was inaugurated by Mrs Palmira Coutinho, the first woman photographer of Goa.

The Kraken and the Road

(This article first appeared in the Joao Roque Literary Journal and was the winning entry under the Short Story category)

The store marks the way to my house. They call it the posro. It’s a small square structure, no bigger than ten paces across; a terracotta tiled roof rises like a pyramid. Rice, rye, and red lentils fill tin cans alongside chickpeas, chillies and cumin seeds, purveyed by a gentle, grey-haired man.

The sun’s beating down. I wheel my bike to the store, turn around, take the steel handlebars in my hands, and put one foot on the pedal, the other firmly on the black tarred road. I’ve been struggling to find my balance for a few hours now with little success.

I focus. The road slopes down before me – a ribbon of freedom for a ten-year-old.

I thrust forward. Gravity does the rest, and I glide down. Slow and wobbly at first. Then pick up speed. The road is now a blur. I’m flying.

Don’t look down or you’ll lose your balance, my father had told me.

I pass a Portuguese-era mansion that stands dark and forlorn, some distance behind a yard overgrown with shrubs. A drunk lives in the balcony that runs across the front façade. That’s what I’ve been told. Snakes too, they warned. I can’t be sure if they were more afraid of the snakes or the vagrant.

On the right, I pass a pit covered in Indian nettle and turnsole, beach bean, touch-me-not and coat-buttons. In the rain, it will fill over – a natural drain. The slope eases into flat road. I’m pedalling now. The wind hits my face, bringing with it the smell of dry grass and salt from the sea – a pleasure in the thick summer heat.

There’s not a soul in sight.

I breeze past mango trees, under electric lines running along the road, past the boarding school gates – the only building in the area, then vacant lots, and slow down before a yellow tiled roof bungalow where an old woman lives alone. A sapodilla tree grows at one corner of her compound. It’s lush brown chickoo fruit still to ripen. Out at the back is a mango tree laden with golden orbs. Opposite, is the prettiest bungalow on the road. White with red trimmings, large French windows open into the garden. With a lawn, flowering plants and plum trees, it belongs in postcards from Europe, not my little coastal village in Goa.

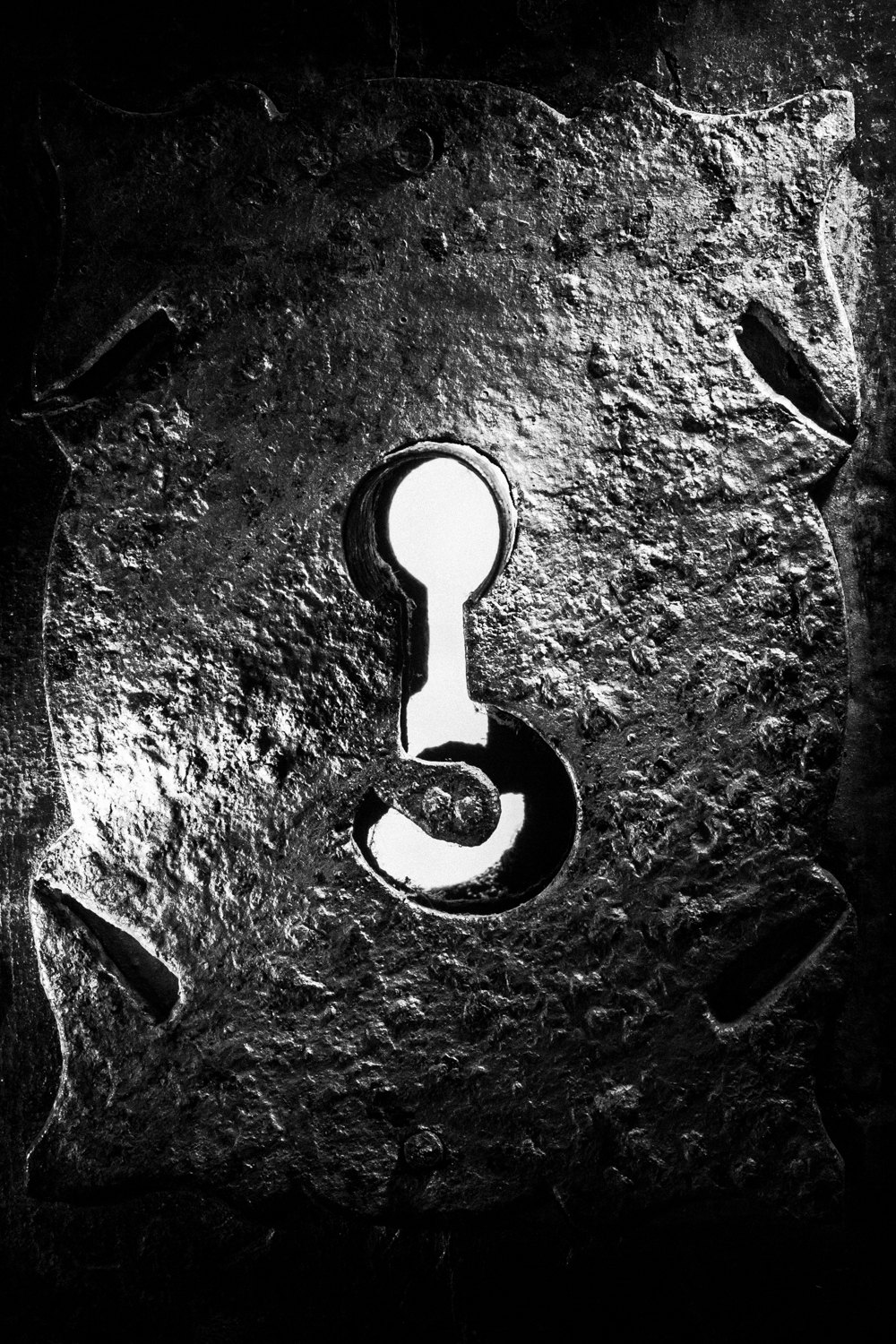

An old well stands some way back. It’s been there from even before the house came up. Haunted. Someone once jumped in, they tell me. Now it’s painted ochre with white outlines for the laterite stones and a red tin shading it. The bullock-cart wheels that make up the compound wall give the house character. They form a semi-permeable perimeter to the house – you’re welcome, but not quite.

“The wheelhouse,” we call it.

I now turn off the road at the majestic banyan tree and head home. This is a desolate patch where Indian plum grow wild. A sandy path cuts through the middle. At night, it’s dark as death and filled with stories of a woman in white, running to the beach at the back of my house.

They tell stories – vivid and colourful.

My bike bumps over the dirt.

It’s freedom. And it’s mine

The Kraken rose from the sea and came calling down my little road. Tentacles flailing, the giant creatures first tore down the old house where the vagrant lived by the posro. In a matter of days, it was gone, the itinerant with it.

New monsters grew out of the ground. First one. Then another. Then another. They devoured the pit. They didn’t even spare the pretty wheelhouse. The Kraken’s tentacles ripped it right out of the ground.

They came for the desolate patch past the banyan tree. Their tentacles were no match for the banyan’s grand roots. A devilish ghoul grew out of the land. I’ll never know what happened to the woman in white. Perhaps she returned to the sea.

Those Kraken – they loved my village. They called it the queen of beaches. I called it home. The demons lived off empty lots and old houses – consuming them to grow monstrosities.

Hotels. Development. Progress. That’s what they said.

New stories, as vivid as the old.

Tentacles sprung from my road and grew all the way to the beach. The bikers came careening. The cars followed. Kids with their cycles were banished by busloads of tourists with wide-brimmed hats. They wore their t-shirts: a setting sun and coconut palms with “I love Goa” in scrawly text, sipping beer from cans which they threw out the window.

The old man at the posro held off the Kraken as best he could – selling his groceries and colas and sweets. But Mickton’s further down the road was bigger and better. They even sold Lay’s.

Convenience, they said.

Soon the old man was gone. I never saw him again. One half of the store succumbed to leather jackets and trinkets from Kashmir. Tandoori chicken and biryani ate the other.

The Kraken were hungry and refused to stop. They soon ravaged the new store further down the road. An even bigger supermarket rose out of a tiled roof bungalow, after the old couple living there died.

With the land gone, the Kraken devoured the tourists. Once they consume the tourists, will the Kraken return to the sea whence they came?

They called this place paradise. The Queen of beaches.

Paradise passes and even queens die.